Lent 2, Year B

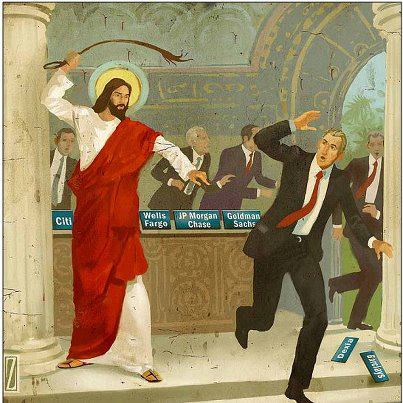

John 2.13-22Though “cleansing of the temple” is the common title for this passage, that is not really what is going on here. “Cleansing” implies something has been cleaned up or changed or reformed. But, in John’s version of the story (and probably in the Synoptics’), Jesus doesn’t appear interested in cleaning up the market system that operated at the

The

story occurs when Jesus enters Jerusalem Israel were required to return to Jerusalem

In

Jesus’ case, he made his trip to Jerusalem after

an extensive ministry in Galilee , preaching a

spiritual and economic egalitarianism. He appears to have entered Jerusalem

But what exactly did he find that enraged him so? According

to John, Jesus found two things: those who were “selling” and those who were “changing.”

The sellers sold things like cattle,

sheep, and doves for the offerings, and the changers

changed money from international currency to local currency. Both were corrupt,

and both were central to the economic idolatry that sustained the nation as a

whole.

The sellers (tous pōlountas) were

those who sold animals for the offerings made at the temple (sorry, but that

was the tradition; they would probably think that I-pads and high heels were immoral

too). People were required to make sacrifices for a variety of festivals and

rites. If you were wealthy you gave a large animal, like a cow or ox. If you

were poor you gave doves or pigeons.[4]

However, to ensure “unblemished” animals, you were required to purchase your

animals at the gate of the temple where the prices were higher than the country-side.

And, as with any regressive tax or price system, the costs tended to be felt more

by the poor than the wealthy. To purchase one pair of doves at the temple was the

equivalent of two days’ wages. But the doves had to be inspected for quality

control just inside the temple, and if

your recently purchased unblemished animals were found to be in fact blemished,

then you had to buy two more doves for the equivalent of 40 days’ wages![5]

Josephus,

the Jewish historian, tells a story of Rabbi Shimon ben Gamaliel (son of

Gamaliel, Paul’s personal spiritual trainer), who went on a campaign against

price gouging. But unfortunately stories of someone trying to protect the poor

from the practice are rare. More common was the reference in the Jewish Mishna that

the costs of birds rose so fast in Jesus’ time that women began lying or

aborting their babies to avoid the required and punitive fees.

The changers (kermatistēs) were needed because neither the animal offerings nor the temple tax could be paid with the

Roman currency in use for most of the national commerce, because it had

pictures (read “graven images”) of the Roman Emperor on them who claimed to be a

god. So, the money had to be changed into usable local currency.

The money changers sat outside of the temple proper,

in the “court of the gentiles.” They bought and sold money as a part of the functioning

of the general economy. Jerusalem Palestine

However, the Money Changers were also corrupt. They

would not only exaggerate the fees they had to charge for the transactions,

they would also inflate the exchange rate. The result was that for a poor

person, the Money Changer’s share of the temple tax was about one day’s wages

and his share of the transaction from international to local currency was about

a half-day’s wages. And that was before

they purchased their unblemished animals for sacrifice and then had to buy them

again (at an enhanced price) because the inspector found a blemish or otherwise

inadequate for the offering.

All

tolled, a one day stay in Jerusalem during one of the three major festivals

could cost between $3,000 and $4,000 dollars in contemporary value, and Jews

were required to attend at least one of them each year. Josephus estimated that

up to 2.25 million people visited Jerusalem

Two

last notes on the tables used by the money changers. First, it's interesting to

note that the word, “table” trapezes, had

just two usages, one was for reclined eating and the other was for conducting

financial transactions. It functioned like a loan office where people invested and

borrowed money, and was sometimes translated simply as “Bank” (cf. Luke 19:23).[8] The second thing is that in Isaiah 65:11 God condemns those tables. He says that people

who forget God and God’s holy mountain are like those who set up “tables” to

“Gad,” the name for the God of wealth.

So, what was Jesus’ response to the situation he found in

Jerusalem

Those who today believe the current global economic system

has failed, often fall into three types. First, those who believe that the system itself is wrong (the very fact of markets creates wealth and

poverty, and that’s wrong); second, that this particular model of economic globalization is wrong (other systems

could be designed to be more fair, but this one is not); and finally, that the

system is fine, but there are abusers of it and discontinuities within it (if

we could just get markets to work right then eventually all boats will be

lifted). Jesus seemed to be in at least the second camp, and maybe even the

first: the very existence of the market at

all was what caused evil. According to what we know of him in this text

itself, he would most likely be against the marketization of life itself.

To make his point stronger,

he followed his actions with the dramatic pronouncement that the temple, which

was the national center of worship, trade, and finance, would be destroyed.[9] In

Mark’s version he even sets up a type of

boycott of all goods and commerce coming into the temple, which starved it of

the funds it was using to fatten the rich.[10]

So how would you preach on this passage?

First, walk through the

story with your congregation, using the background information in this essay.

Most people, even if they know of the story, have no idea of the economic ramifications

of the “cleansing” story. Given the confrontation at the temple, it is no

wonder that the Synoptics believed it to be the key event that turned the

authorities against Jesus.

Second, tie this ancient oppressive

system to today’s global system that continues to keep two-thirds of the world

in poverty. Read up on how the austerity programs imposed on poor countries as

a requirement of receiving debt relief has in many instances actually caused more poverty, and weakened their ability

to pay those debts. The recent revolt in Greece is a good example of that which

you can cite.

Another less frequently

reported example is the Ebola-hit countries of West Africa. For decades the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) and other multi-lateral financial agencies, have imposed

strict restrictions on these countries’ public spending so that they can

continue making payments on ancient loans (often taken out by long-dead

dictators for personal use). The result has been that these countries have had

to make dramatic cuts in spending on infrastructure, education, and health care, which meant that when the crisis

hit, their resources with which to address the problem had been seriously

diminished.

For the last two years the

faith-based Jubilee USA Network has been lobbying the Obama Administration and

the IMF to get them to cancel at least a portion of the debt burden that is

crippling these countries. Finally, in February of this year, the IMF announced

that it would release $170 million in debt-relief (and more in less restrictive

loans) to three Ebola-affected countries—Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. That

the relief will be a major contribution in their ability to turn back the

epidemic more quickly than experts had predicted. This would be a good story to

cite for your congregation, and you can find updates and other stories about Jubilee’s

work on their web site, www.jubileeusa.org[11]

You could then conclude by

saying that as people of faith, we cannot ignore the world beyond our doorstep.

God stands with the powerless against the powerful. Isaiah attacked those who

were rich for their opulence: “Their land is filled with silver and gold, and

there is no end to their treasures” (2:7a). Jeremiah said they “have become

great and rich, they have grown fat and sleek. They know no limits in deeds of

wickedness” (2:8). Amos said that unchecked, the wealthy would “trample on the

needy, and bring to ruin the poor of the land” (Amos 8:4, cf. 2:7, 4:1).

According to Amos, the special, spiritual sin of the economically powerful was

that they could lounge on couches, eat lambs from the flock, drink wine from

bowls, but “are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph [their poor neighbors]”

(6:4-6).

Jesus railed against the abuses of power by Herod and the religio-political leaders of Jerusalem. Both he and his cousin John demanded great financial sacrifices of those entering and modeling the coming “Realm” of God. I suspect that a number of us, of whatever religious stripe (not all Christian) could see ourselves as their offspring and followers, if we understood this as the path they were leading us in. With a world still wracked in pain today we can do a lot worse than to walk with faith in their footsteps.

[1] Among others, see Malina & Rohrbaugh, Social-Science Commentary on the Gospel of

John, “This incident represents ... prophetic actions symbolizing the

temple’s destruction,” p. 73. And John Dominic Crossan, The Historical

Jesus, The Life of a Mediterranean Peasant (San Francisco: HarperCollins,

1992), who says it attempted

to symbolically end the temple’s “fiscal, sacrificial, and liturgical

operations,” p. 358.

[2] The Synoptics are probably more historically accurate

when they place the story at the end of their Gospels instead of at the beginning

as in John. But all four agree that it is his first visit.

[4] You may recall that Jesus’ parents, who were very

poor, brought two turtle doves for the dedication of Jesus (Luke 2:24).

[5] Jerry Goebel, “The Gospels: The testimonials of Jesus

Christ” onefamilyoutreach.com/Bible/John/jn_2_13-25.htm (2002).

[6] Ched Myers, Binding

the Strong Man (Orbis, 1991), p.

301.

[7] Jerry Goebel, “The Gospels: The testimonials of Jesus

Christ,” http://onefamilyoutreach.com/Bible/John/jn_2_13-25.htm, 2002.

[8] It might be interesting to learn that according to Mel Gibson’s movie, “The

Passion of the Christ,” Jesus invented the “tall table” to be used for sitting.

[9] This is debated, but see above on n. 1. Within the

ancient texts the range runs from Mark, who denies that Jesus said it so many

times that it resembles “damage control,” to Thomas (71), which simply states

that Jesus said it with no qualifications. Crossan believes Thomas to be the

more historical because it is simple, straightforward and unapologetic.

[10] Mark 11:15-19. See

especially, Mark 11:16 “and he blocked (aphiēmi) anyone from bringing any goods, equipment, or vessels (skeûos) from coming through the temple.”

[11] For an article specific to Ebola-related

debt relief, follow this link: http://www.jubileeusa.org/press/press-item/article/imf-plan-offers-170-million-in-debt-relief-for-ebola-impacted-west-africa.html

2 comments:

Great article, Stan!

I've concluded that whenever Jesus pronounces forgiveness in Galilee according to the Synoptics, he's actually relieving someone of paying the debt-penalty established on top of the torah.

NT forgiveness generates economic freedom.

Russell,

Thanks.

You may well be right about that. A number of scholars have noted that the language of forgiveness in the New Testament is based on the debt forgiveness passages of Leviticus 25 and Deuteronomy 15. Luke's version of the Communion language makes this pretty clear, "Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.

Stan

Post a Comment